In 1466, in a dusty workshop in Florence, a master painter takes on a new apprentice. The boy is fourteen years old, the illegitimate son of a notary from a nearby village. The master teaches him how to mix colors, how to hold a brush, and how to observe light as it falls on fabric.

As it would turn out, this apprentice was not quite an ordinary teenager.

Instead of merely repeating the master’s movements, Andrea del Verrocchio watches as he records everything he sees. Draws hands from all angles. Observes how drapery folds differently on different fabrics. Asks questions about why shadows fall this way and not that. Why does light reflect differently from water than from glass?

When they worked together on “The Baptism of Christ,” Verrocchio gave the apprentice the task of painting an angel in the corner. A smaller job. Ordinary. But when the apprentice finished — the angel shone so differently from the rest of the painting that Verrocchio realized: this boy already sees the world in a way I cannot.

Leonardo’s angel on the left, his teacher’s angel on the right

Leonardo’s angel on the left, his teacher’s angel on the right

And Verrocchio, instead of stopping him, opens up space for him. Gives him more complex tasks. Places him to work on parts of paintings that require more than mere technique. Watches him grow and guides him toward his own heights.

That apprentice was Leonardo da Vinci.

And we owe him far more than the Mona Lisa (though she is magnificent). We owe him anatomical drawings that changed medicine — he dissected corpses in the dark to understand how muscles work beneath the skin. We owe him sketches of flying machines, bridges, and military devices that wouldn’t be built for another 400 years. But we owe him most for the approach to learning he taught us: record everything you see, question everything you think you know, connect what others keep separate. Art and science. Beauty and function. Observe, test, connect, record.

“Learning is the only thing the mind never exhausts, never fears, and never regrets.” -Leonardo da Vinci

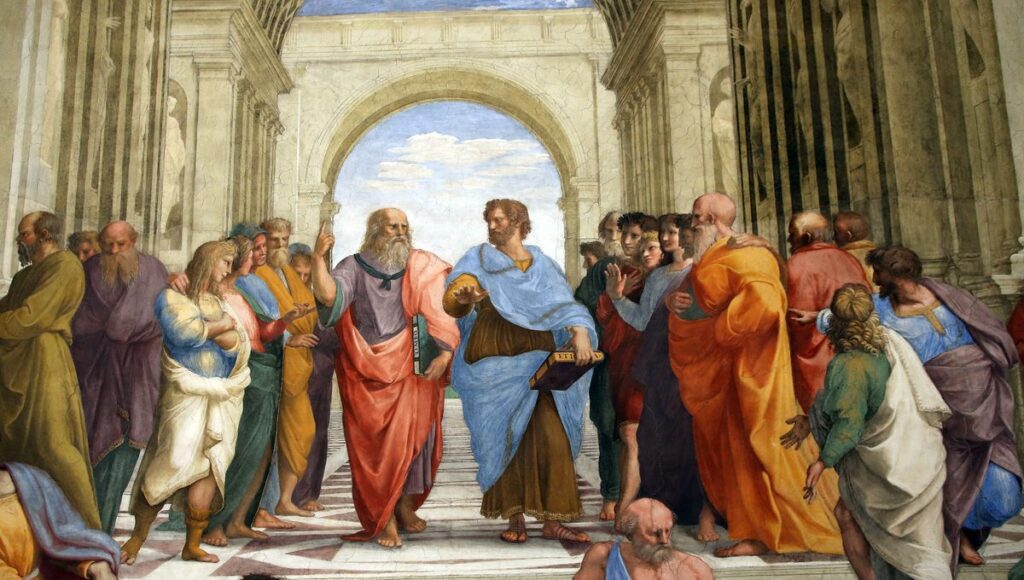

2000 Years Earlier, in Athens

One man walks through the city, accosting random passersby with questions. They say he was unpleasant and awkward in appearance, of a strange nature. He doesn’t teach. He doesn’t preach. He converses. He asks merchants about justice, politicians about wisdom, and priests about the gods. And he doesn’t accept the first answer he gets. He deconstructs every belief, question by question, until the interlocutor realizes how little they actually know and what they don’t know.

This irritates people. In the end, they condemn him to death.

One young man spent years listening to these conversations and the way this other master conducted them. Socrates, that magnificent master of sharpness, taught him to think. To ask questions. To not accept answers without explanation, nor others’ convictions (and especially not his own) without knowledge and discussion.

That young man was Plato.

And we owe him more than most know. Not only in the realm of philosophy, but also the first blueprints for state organization (those ideas live in many laws today). We owe him the metaphor of the cave — the story about shadows on the wall that we watch thinking they are reality, because we are only aware of the shadows, not of what/who casts the light to obscure the truth. We owe him the Academy, the first institution where knowledge is transferred systematically, where there are teachers, students, and open space for thought.

“I know that I know nothing, and therefore I know more than others.” — Socrates

And in that Academy, twenty years later, one young man learns from Plato. Absorbs everything. Plato asks him to think. To question. To build his own method.

That young man was Aristotle.

And we owe him the very structure of reasoning — logic, the way we prove anything through syllogism (all men are mortal, Socrates is a man, therefore…). We owe him the first systematic classification of nature, the idea that the world is understood through observation, not just thinking. He founded the Lyceum and laid the foundations for more scientific disciplines than anyone before or after him.

“Those who know, do. Those who understand, teach.” – Aristotle

Aristotle, later, becomes a teacher to a young prince from Macedonia. He teaches him ethics, politics, philosophy, and the limits of power.

That prince was Alexander the Great.

And we owe him the world as we know it. In 13 years, from Macedonia to India, he connected East and West in a way no one before him had attempted, joining cultures, economies, and cities that bore his name (over 20 Alexandrias). He died at 32, but through his short life created the foundations for a civilization that would shape the Mediterranean for the next thousand years.

Socrates → Plato → Aristotle → Alexander the Great.

Four generations.

Each went further than the previous.

But none would have reached there had they not stood on the shoulders of those who came before them.

The Pattern That Repeats

When Isaac Newton wrote to his rival Hooke that he “stood on the shoulders of giants,” he sounded humble to some. Though I believe he was precise. Newton didn’t arrive at the laws of gravity alone. He built on Galileo’s observations of falling bodies, on Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. He saw further, but because he stood on the shoulders of his great predecessors and thus saw more and broader than they, just as we stand on their shoulders and on the shoulders of all who left us knowledge as heritage.

Every great individual success is woven with the knowledge and experiences of others.

Every person who reached far stood beside someone who saw further at that moment.

Why I’m Sharing This With You

Today, two-thirds of Fortune 500 leaders say a mentor was crucial to their success.

Not magic, not some extraordinary story about luck or an exceptional university they graduated from. A person. Who was where they were, only trying to reach, and helped them go far, all the way to fulfilling their dreams.

Since we exist as a species, those with a broader perspective have stood beside those who want more. Latin magister. German Meister. Sanskrit guru. Always the same idea: someone who has already walked the path that others are just beginning to walk and who is ready to broaden perspective, direct, encourage, and guide.

If at life’s crossroads we pause and think it would be faster to go further with a mentor, it would be good to have answers to the following questions:

Who are these people?

How do we recognize them?

And what does mentorship actually entail?

I write about these questions in the following text.

***

And here’s the link to the previous text in the mentorship series: Do You Need a Mentor?

2020

2020

Comments