Gratitude has become one of the most loudly celebrated virtues of our time. We are taught to be grateful. To remember what we have. To start the day with affirmations. To find the lesson in everything. To look for the good even when things are clearly bad.

And yes, all of that makes sense.

But only up to a point.

The problem begins when gratitude stops being a tool for growth and becomes a substitute for reaction.

At that point, gratitude no longer heals.

It poisons. Us—and the whole world around us. Why gratitude is not (always) a good thing?

Gratitude as a sedative of conscience

Among good people, gratitude rarely comes from weakness. It comes from strength. From breadth. From the capacity to understand, forgive, integrate, and survive.

And that is precisely why it is dangerous. For such people, gratitude becomes:

- a sedative for conscience

- an anesthetic for anger

- a substitute for boundaries

And this is especially dangerous because it comes from good people.

Bad people do not misuse gratitude. They simply ignore it. Gratitude is misused by good people—and that is how a larger systemic problem is created.

A bad person causes damage locally.

A good person who does not react legitimizes the damage.

Gratitude that comes too early kills diagnosis

The contemporary narrative around gratitude does not come from nowhere. It comes from highly respectable sources. Thinkers I deeply respect—such as Martin Seligman, Robert Emmons, and Sonja Lyubomirsky—as well as institutions and platforms like Harvard Health, the American Psychological Association, and the Journal of Positive Psychology, are full of research, articles, and recommendations about the power of gratitude.

And these brilliant people are not wrong.

Gratitude does reduce stress, increase a sense of meaning, strengthen resilience, and help us cope with difficult circumstances. This is empirically proven, important, and effective.

But it is not the whole truth.

Because in the popular interpretation of these powerful ideas, we rarely ask questions about action, boundaries, and power. Gratitude is almost exclusively treated as an intrapsychic tool—a way for the individual to feel better within given (often unfavorable) circumstances.

What is systematically missing is the question: Are those circumstances unjust, harmful, or changeable—and what is our responsibility toward them?

That is where the problem begins. The problem lies in what is omitted. In what is not deepened.

Today, gratitude is widely promoted and applied before reaction, rather than after it. And gratitude that comes too early kills diagnosis. If we do not see harm as harm, we dull the very edge of change that is required.

Without diagnosis, there is no intervention.

Without intervention, harm becomes normalized.

The septic tank of modern life

Imagine living in a septic tank—but wearing a protective suit.

The suit has air filters, so it smells less. It has a visor, so the waste starts to resemble beautiful shapes—like clouds in the sky. It becomes tolerable. Over time, even comfortable.

But the septic tank remains what it is.

And, most importantly, it continues to fill.

Gratitude, in its popularized (and populist) form, does not drain the tank. It merely allows us to stay inside it longer—and survive. At that point, gratitude stops being a virtue. It becomes a tool of harm.

Not good for us—and certainly not good for the world around us.

“Grateful for harm” and “ungrateful for good”

This is the symmetry of the pathology.

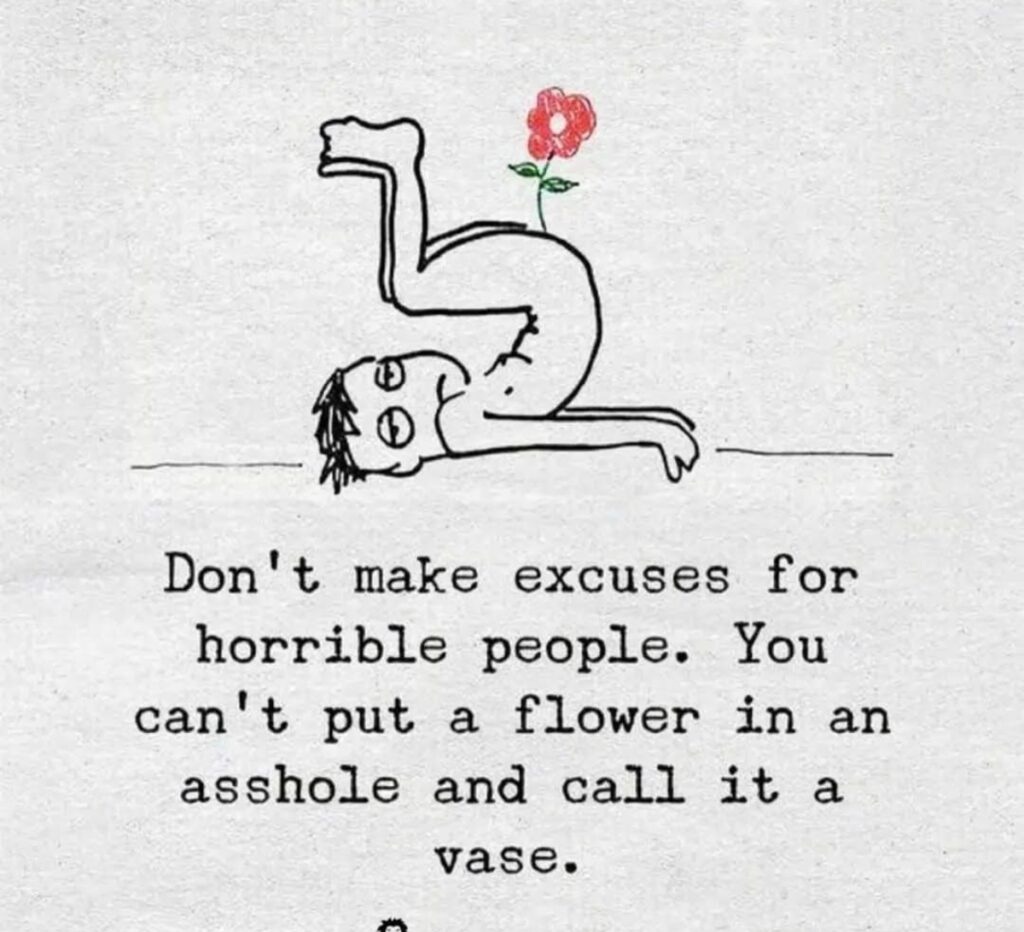

On one side are people who are grateful for harm. They call injustice a lesson. Bad relationships growth. Systemic stupidity an “opportunity.”

On the other side are people who are ungrateful for good, because they experience it as something they are entitled to. As a standard. As a reward.

One side erases the bad.

The other erases the good.

Both erase reality.

That is why gratitude is not a moral virtue in itself. Just as ingratitude is not always a flaw. Both are tools. And every tool must be properly directed.

Misused tools cause damage—and unfortunately, we misuse most of them.

I am not obliged to be grateful. I am obliged not to be.

This needs to be said clearly—and loudly.

I am not obliged to be grateful for injustice.

I am obliged not to be.

Gratitude toward injustice is not nobility. It is moral confusion. Evil has no right to our gratitude. Injustice has no right to our gratitude.

Gratitude is not owed to the situation. Gratitude is owed to ourselves—only if and when we change the situation for the better. Only after we transmute it.

I am not obliged to be grateful for injustice. I am obliged not to be.

The central developmental question we keep avoiding

The question most often asked in the populist gratitude narrative is:

How can we make what is bad more bearable?

The developmental question I ask, as a growth guide, is different:

How can we turn what is bad into something better?

How can things actually improve?

Being an observer who “does not let things affect them” is not the end of growth. Being a self-creator who beautifully packages everything and carries it silently is not the end of growth. These are sophisticated forms of stagnation. If we ask only how to endure, we stay where we are. When we ask how to make things better, we react.

And only then do we grow—both we and the world around us.

Why good people carry greater responsibility

When good, conscious people do not react, the cost is not paid only by them.

It is paid by those who do not have the capacity for gratitude. Strong, conscious, grateful people survive. Weaker, more sensitive people—without that capacity—break.

And then come drama, trauma, and the collapse of personal systems.

That is why reaction is not a personal matter. Responding to harm is a collective ethical obligation.

We react not only for ourselves. We react for those who cannot. For those who lack the capacity for blanket gratitude and endless life in a septic tank. For those without protective suits. For those who are not even aware they are drowning in waste.

Let’s take inventory

If our boss publicly and unjustly attacks us,

if a colleague exploits and takes credit for our work,

if a partner ignores us for months and calls it “a difficult phase,”

if a client refuses to pay what we honestly earned,

if our child suffers injustice at school and everyone says “don’t rock the boat,”

if people constantly cut us off, step over us, take up space—and we tell ourselves it’s “not worth reacting,”

if the system grinds us down and we stay silent because “we still have more than many”—

and we say to ourselves,

“Well… who knows what this is good for,”

and we do not react, do not set a boundary, do not attempt to change anything—

we are not choosing good.

We are choosing to let the septic tank fill a little more.

And it is not only us who are suffocating.

We all are.

You.

Me.

Us.

Them.

A better ending—and a better beginning

Gratitude that comes too early kills diagnosis.

Without diagnosis, there is no intervention.

Without intervention, harm becomes normal.

That is why I am not obliged to be grateful for injustice.

I am obliged not to be.

Gratitude is not owed to evil.

Gratitude is owed to ourselves—only after we react.

And now comes the question we can no longer avoid.

If we ask only how to endure, we will remain where we are.

If we ask how to make things better, we will have to move.

So do this.

Identify one situation in which you recently chose gratitude instead of reaction.

Not three. One.

Then do one thing:

- say no

- set a boundary

- speak what you have been holding back

- send the message you keep postponing

- do not step aside in line

- do not stay silent about injustice

- do not rationalize one more time

You do not have to win. You do not have to change the world. But you do have to stop quietly sustaining it in a broken state. Growth does not begin with gratitude. Growth begins with reaction.

And only then—after reaction—does gratitude truly belong.

2020

2020

Comments