Hello. Who are you?

We became numbers. As many times before, an invention or fiction made up to serve us has enslaved us. Instead of ruling numbers, we are their humble servants. We also teach our children to serve them, so some of the first questions we prompt children to ask new friends are: how old are you, how many siblings do you have, what grade are you. When we want to evaluate them, we ask them what grade they got, how many pluses, how many more fives or aces were in the class, what is their average grade and how many friends were with them in the park. They wake up to a number, in school, they are limited by the number of minutes of a school class, by the number of minutes they have to do the task. They are arranged in classes according to the numbers of the years they have passed, and the number with which they leave school will be a numerical ticket for enrolling in a new school.

We ourselves, as adults, are even more servants to numbers. We are a unique ID number, tax identification number, passport number, ID card and driver’s license number, ordinal number in the police or bank; we are our date of birth, address, number of properties we own; we are years of service, number of years of work in one company, weight & height, age, calories, measurements, and volumes; we have mean values in blood findings, number of shoes & confection number. And as we blinked, the numbers enslaved us. Just like some other inventions, such as social networks, state systems, and money itself, which is the biggest fiction of all. Sometimes it seems to me that we would doubt our own existence if we did not have these powerful numbers to testify about our existence.

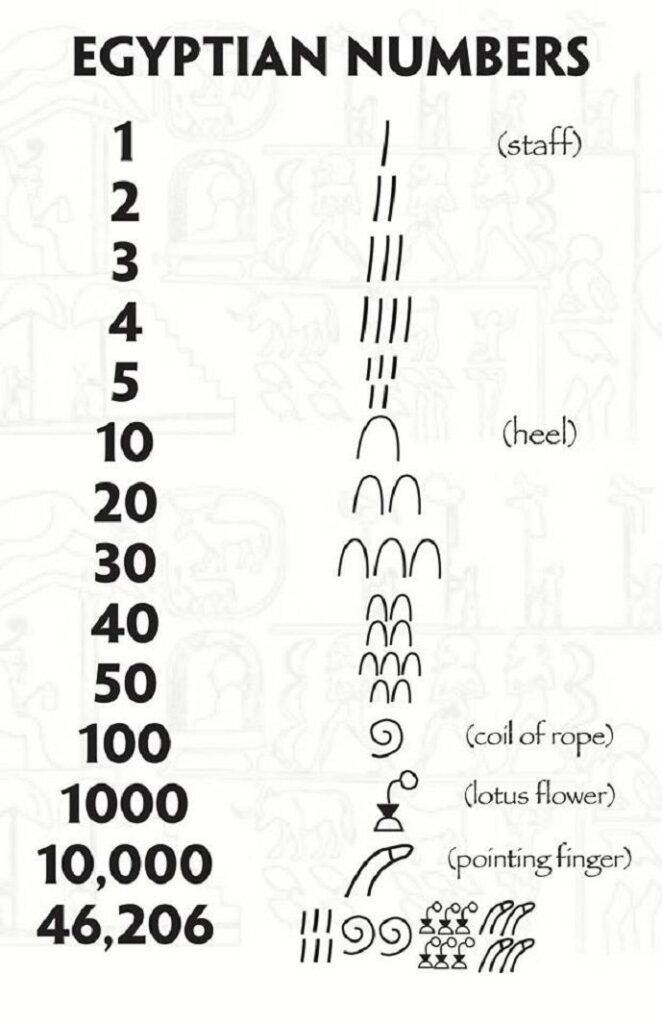

The need to add/sum up (gather ourselves), compare, calculate, has been existing for millennia. The first “numerical records” were found in the caves of South Africa, as vertical lines (similar to the Roman number one), engraved on the bones of baboons. These records are about 35,000 years old. Numerical systems have been improved throughout history since Ancient Egypt (characters for numbers 1, 10, 100, 1000 to a million). The Romans further developed their numbers, the ancient Greeks experimented with a “number” that would represent “nothing” because without nothing we would notice a small difference between one and a million. Without value for “nothing”, we wouldn’t have millionaires and billionaires, because, obviously, their wealth is measured by numbers and money, invented concepts that we give meaning to by accepting them. Over time, we turned even “nothing” into something thanks to the Mesopotamians, the Mayans, and finally the Indians in the ninth century AD. That was when zero (nothing) became something.

The need to add/sum up (gather ourselves), compare, calculate, has been existing for millennia. The first “numerical records” were found in the caves of South Africa, as vertical lines (similar to the Roman number one), engraved on the bones of baboons. These records are about 35,000 years old. Numerical systems have been improved throughout history since Ancient Egypt (characters for numbers 1, 10, 100, 1000 to a million). The Romans further developed their numbers, the ancient Greeks experimented with a “number” that would represent “nothing” because without nothing we would notice a small difference between one and a million. Without value for “nothing”, we wouldn’t have millionaires and billionaires, because, obviously, their wealth is measured by numbers and money, invented concepts that we give meaning to by accepting them. Over time, we turned even “nothing” into something thanks to the Mesopotamians, the Mayans, and finally the Indians in the ninth century AD. That was when zero (nothing) became something.

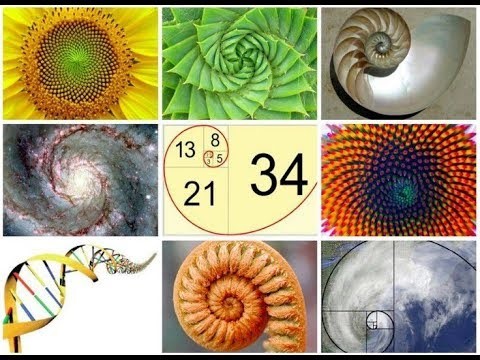

Numbers are an integral part of nature, but only humans are enchanted by numbers. Numbers predetermine the number of petals of different flowers, the number of wings, legs, or strings in a pineapple, for example, whose rind is “divided” into two rows of spirals – one clockwise, the other counterclockwise. The number defines the pineapple because the weight of the pineapple determines whether there will be 5 and 8, 8 and 13, or 13 and 21 spirals. Notice something interesting here now – the spirals on the pineapple are 5, 8, 13, 21. What do you think about those numbers? Each is larger than the previous, yes; but each is the exact sum of the two previous ones, which is a more fascinating conclusion. This is a form of numerical sequence well-known to nature, it is called the Fibonacci sequence. Trees, from trunk to branches, grow according to this model; the arrangement of seeds in sunflower follows this model, as well as the number of bees in the next generation. Sacred geometry or golden ratio, [pre]defines various parts of the human body (for example, fingers in the hand or proportions of the face) and natural phenomena (at the micro and macro levels such as hurricanes, cyclones, constellations), but does not determine them.

Numbers are an integral part of nature, but only humans are enchanted by numbers. Numbers predetermine the number of petals of different flowers, the number of wings, legs, or strings in a pineapple, for example, whose rind is “divided” into two rows of spirals – one clockwise, the other counterclockwise. The number defines the pineapple because the weight of the pineapple determines whether there will be 5 and 8, 8 and 13, or 13 and 21 spirals. Notice something interesting here now – the spirals on the pineapple are 5, 8, 13, 21. What do you think about those numbers? Each is larger than the previous, yes; but each is the exact sum of the two previous ones, which is a more fascinating conclusion. This is a form of numerical sequence well-known to nature, it is called the Fibonacci sequence. Trees, from trunk to branches, grow according to this model; the arrangement of seeds in sunflower follows this model, as well as the number of bees in the next generation. Sacred geometry or golden ratio, [pre]defines various parts of the human body (for example, fingers in the hand or proportions of the face) and natural phenomena (at the micro and macro levels such as hurricanes, cyclones, constellations), but does not determine them.

Nature is not determined by numbers. Humans accepted that numbers determine them. – Dragana Djermanovic

Are we really slaves to numbers?

I acknowledge the great importance of numbers, I blame us for the weaknesses [of the mind] to rule over them. Burdened with numerous misconceptions, prejudices, and common mental shortcuts, we use numbers to justify bad assessments, poor investments, the logical consequences of our recklessness, and to reinforce our faulty theses. When it comes to numbers, we are terribly unhandy and clumsy, even irrational. In his book “The Art of Thinking Clearly”, Rolf Dobelli cites the results of experiments which confirmed that a person will walk ten minutes more to buy food for ten euros less, but almost no one thinks to “take a ten-minute journey to the other end of the street to pay 979 euros for the same suit instead of 989.” The author then writes: “This is an example of irrational behavior because ten minutes is ten minutes, and ten euros is ten euros.” The same book states that people are equally afraid of a 99% chance as they are of a 1% chance of contamination by toxic chemicals – that is, we accept only zero risk. Zero risk, as well as zero as such – is a fiction, but we are simply not able to see it clearly.

Nasim Taleb deals with numbers in different ways, and in his book “Skin in the Game”, he states that analysts make mistakes far more often than they are right. Over time, they become more relaxed in their assessments, they find it easier to “shoot” with numbers and probabilities because no one calls them for accountability after a mistake, and in case they find a grain like a blind hen and guess, they are celebrated by everyone and enchanted by themselves. Taleb further proposes introducing an obligation to pay a certain amount of money in a “fund of erroneous forecasts”, believing that they would start evaluating a bit more carefully. And for numerous failures of analysts in health care, sports, economy, we would at least raise enough money to teach future analysts to be more careful in thinking and drawing conclusions.

In his book “Factfulness”, Hans Rosling states that chimpanzees (yes, monkeys) answer more accurately than humans to questions about percentages and life in numbers in general.

Here is how numbers deceive us in human resource management as well. We would say that more people in the team increase productivity, but that number deceives us as well. The more people in the team, the lower the productivity, so if one person works on a task in the team, he gives his maximum (which is, to be precise, 96%). Two people will not work twice as well, and when eight people are hired, each of them uses only 49% of their power/capability (R. Dobelli). This phenomenon is called “social loafing” and is more interesting because, apart from the fact that the numbers seduce us here, it shows how we behave in a group, how our effectiveness decreases, but also how it never drops to zero – not because “nothing” does not exist, but because that way we would draw attention to ourselves and cause social resentment and other consequences. We will work just as much as it is necessary, for others not to notice how much less effort we exert, and so that it doesn’t happen that someone notices that we don’t work at all. The Japanese solved this problem and beat the numbers by giving each team member a specific task that is measured and monitored separately, so the efficiency of each employee is close to 100%, not because people are more hard-working, but because their laziness would be easy to notice. Numbers work for them because not all nations enslave numbers equally. However, there are countries in which they don’t know how much work is done, for example, in public administration services, but also they don’t know how many people work in that sector. To some, every mathematics is higher mathematics, and numbers are the most commonly manipulated and deceptive assets.

Here are a couple of examples in which we adopt numbers without sinking into the matter, and which do not say anything reliable: “The new restaurant is top class! It is receiving praise by everyone!” or “People live better, the average life expectancy is 70 years, and at the beginning of the twentieth century it was around 30” or “Our planet is overpopulated. We need fewer births ”or “As many as 1,000 people died!”. In the following text, we will explain why all these and many similar statements really don’t tell us much. To the list of frequent manipulations with numbers, I’m adding: “We are recording a growth of 4%”, and then “The vast majority trusts him”, or “There are 1000 open jobs positions”. Some of the more well-known numerical deceptions are “Polls show” and the famous “Studies have confirmed”.

How to use numbers instead of being enslaved by them

The best way to know more and better understand the world is to think with your own head. By this I don’t mean you should have an opinion, which is easily adopted (through the media and social media), bought (in lectures, in schools, and even on the Internet), to steal it from others (by taking over whole concepts and clarifications that someone else – know them or not, they will summarize and share it in a column, video, TV guest appearance or on their wall on the networks). Thinking and having an opinion are two completely different things. The first is active – it involves analyzing, comparing, questioning, monitoring, and checking so that you can form your opinion based on all that. Having an opinion, on the other hand, is a passive category – it is not knowledge either, and whatever it is, it is not yours.

Thinking and having an opinion are two completely different things.

And who are you, if you don’t think? The ability to think, plan, and imagination make us the most fascinating living species on this planet since its genesis four billion years ago – and there were many living species in that period. What makes us the most exceptional, what brought us here where we are, to manage almost everything in the best possible way, even to walk in the space, is what will make us significant in the future when every office and every home will have a supercomputer, that we will not fight against with opinion, but with ability to think – in colors, richly, unpredictably and with curiosity. To think, you have to learn. Thinking and learning are easiest by asking questions. Curiosity may have killed some unfortunate cat, but it could definitely save us.

Here’s how we beat the numbers with questions and how we can easily take at least a bit more control over our lives.

One of the favorite facts I researched is that today women give birth to an average of two children (2.5) and that a hundred years ago they gave birth to about five kids. The growth of the population of our planet by as much as 6 billion in the last 120 years is not a consequence of birth, but the result of social progress. That progress meant that the mortality rate of children under the age of 5 dropped drastically from 44% to 4% (in the nineteenth century, 44 out of 100 children would have died before the age of five, while today that number is 4 out of 100). This progress means that one does not need to have many children to maintain the household, but also that children can be educated, as well as mothers who, in addition to their own education, can pay more attention to their children. That progress brought vaccines, penicillin, preventive methods and radiology, and many other handy inventions, which we learned to master and use. We have not learned this about numbers even though they are the fruit of our minds. It is obvious how “hollow” is the claim that “Our planet is overpopulated. We need fewer births.” Although far more people live on the planet, this information is not a consequence of birth and thus correlated and placed in a causal relationship, it is a classic example of deception to which we are exposed without our will, and subject to our will. If someone is better, compared to whom; if someone is bigger, on what basis; if something is scary – for whom exactly?

When you read or hear the statement “We are recording a growth of 4%” ask (yourselves):

- Can we do more?

- Who is recording higher growth and why?

- Growth of 4% is the growth of what exactly?

- How does the reflection of growth look like?

- Who can measure it and do different measures show different results? And why?

You can enquire the statement “The vast majority trusts him” as follows:

- Who makes the majority?

- How do we know it is vast, and how can we confirm that it is the majority?

“There are 1000 open jobs positions” can also be examined:

- How many job positions were closed in the same city in a certain period and why?

- What will be the salary of these people?

- For what period and under what conditions are they employed?

- By what criteria?

- As a city/state, do we get the same / less / more with this employment than with employment in another company?

Whenever you hear: “Polls show”, “Scientists believe”, and “Studies have confirmed”, be sure to ask additional questions because that is the easiest way to instill opinions into our minds with a delusion called anonymous (false) authority. Even if the authority is not anonymous, that still does not mean that it is credible. Here’s how to approach it:

- Which polls? Which scientists and which studies?

- Are there polls and studies that dispute the same?

- What are the arguments of scientists who negate this?

- Did the poll/survey and study only confirm that or did it come to some more conclusions?

- Who funded the pole or study?

- Which similar polls and studies have been conducted by the same organizations and with what conclusions?

- Is there a pattern in their conclusion? Why?

Of course, if we don’t have time, interest, or knowledge, we will not either want or be able to ask questions. Remember that just because you don’t ask questions, for maybe you are not interested in it, or you don’t have knowledge about it or no time for it, doesn’t mean that other people’s opinions, which are definitely and constantly planted in your mind, won’t work. That is how we begin to have an opinion about everything, thinking less and less about what really is important to us.

Rudyard Kipling wrote a wonderful poem about six sincere “people”:

I keep six honest serving-men,

(They taught me all I knew).

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

I send them over land and sea,

I send them east and west…

Five golden rules

- Regarding each number you hear, ask for at least one more piece of information that will put that number in context.

- Do not rush to have an opinion. It’s perfectly fine that there are topics, people, and areas you don’t have an opinion on.

- Even when you think, when you think of something and form your opinion, remember that it is only your opinion, formed from your beliefs, based on information that attracted your attention (because of the preconceptions you have about everything & everyone). There is no complete certainty, and therefore no permanent opinion and no universal truths. Truths are a personal thing, the same is with opinion.

- Arm yourself with curiosity. Let your conversations, consuming media content, and dealing with a topic that interests you be adorned with a desire to know, not a desire to be smart, to be right, or to prove that your opinion is better than others.

- It is not a problem to change your opinion, after you think better, after the circumstances and your knowledge change over time. My wise father used to say that only stupid and dead people do not change their opinion. He liked to think.

Master the numbers, it’s easier than you think. But, above all, manage yourself. Self-control is a bit of a difficult hike, but a hike worth living.

✻ What do you think, how do you think? Do you think it could be better? You can book a lecture, workshop, or combination on the topic of this text for yourself, your company, or an event you are organizing via the following link. The text is an excerpt from my group of products “Mind your mind”. How to think more clearly, literally, how to resonate and create original ideas, and how to manage your business and yourself better, how to make wiser decisions and make better sales – all this can be learned. Over a thousand people and hundreds of companies I have worked with so far, confirm that there is a way. Of course, only if you think you should. Think about it.

2020

2020

Comments